Scientists have made an exciting discovery which could lead to a new understanding and treatment of cervical cancer patients.

University College London (UCL) scientists have discovered that cervical cancer can be divided into two distinct molecular subgroups. They found one is far more aggressive than the other, and this new research could revolutionise cervical cancer treatment and understanding.

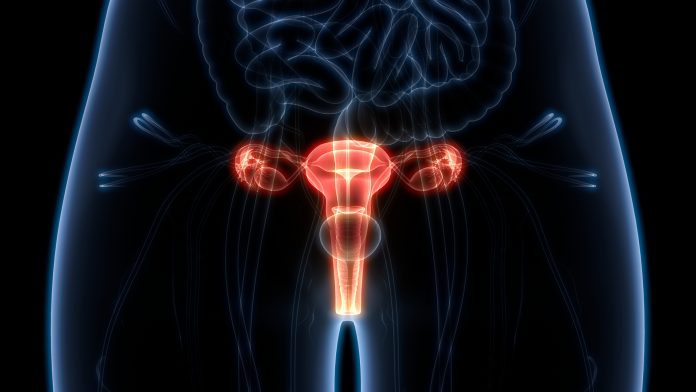

Cervical cancer is cancer that’s found anywhere in the cervix, and is a major cause of cancer-related deaths in women. The main cause of cervical cancer is an infection from certain high-risk types of human papillomavirus (HPV), which can be acquired by any skin-to-skin contact of the genital area, vaginal, anal, or oral sex, and sharing sex toys. Current cervical cancer treatments will depend on multiple factors, but typically include surgery, chemotherapy, or radiotherapy.

The researchers employed a multi-omics approach

In the study, the researchers applied a multi-omics approach. They analysed and compared a combination of different markers, including DNA, RNA, proteins, and metabolites, in 236 cervical squamous cell carcinoma (CSCC) cases. They used publicly available data from the United States.

The analysis revealed that US cancers fell into two distinct ‘omics’ sub-groups named C1 and C2. The researchers found that C1 tumours contained more specialised white blood cells called cytotoxic T cells, known to be potent serial killers of tumour cells. They also discovered that patients with C1 tumours would have a stronger immune response within the tumour microenvironment.

This led to the researchers questioning whether the two subtypes affect patients with cervical cancer in different ways and whether the information could power new cervical cancer treatments.

Could the new data lead the way for cervical cancer treatment?

The UCL researchers expanded their team with scientists from the universities of Kent and Cambridge, Oslo University Hospital, and the universities of Bergen and Innsbruck. They derived molecular profiles and analysed clinical outcomes of a further 313 CSCC cases held in Norway and Austria, as there was a more detailed patient follow-up available.

By integrating the analysis, the researchers found again that nearly a quarter of patients fell into the C2 subtype and that C1 tumours had more killer T cells than C2 tumours. The data also showed that C2 was more clinically aggressive. The data found was similar across the US and European cohorts.

The team also analysed a further cohort of 94 Ugandan CSCC cases. They found that C2 tumours were most common in HIV-positive patients.

The researchers suggest that the C1/C2 grouping appeared to be more informative than the type of HPV present. Cervical cancer can be caused by at least 12 various ‘high-risk’ HPV types, and there have been conflicting reports as to whether the HPV type present in cervical cancer influences the prognosis for the patient.

The study suggests that whilst certain HPV types were commonly found in either C1 or C2 tumours, the prognosis was linked to the group to which the tumour could be assigned, instead of the HPV type it contained.

Co-corresponding author, Tim Fenton, Associate Professor in Cancer Biology at the School of Cancer Sciences Centre for Cancer Immunology at the University of Southampton, said: “Despite major steps forward in preventing cervical cancer, many women still die from the disease. Our findings suggest that determining whether a patient has a C1 or a C2 cervical cancer could help in planning their treatment since it appears to provide additional prognostic information beyond that gained from clinical staging (examining the size and degree to which the tumour has spread beyond the cervix at the time of diagnosis).

“Given the differences in the anti-tumour immune response observed in C1 and C2 tumours, this classification might also be useful in predicting which patients are likely to benefit from emerging immunotherapy drugs such as pembrolizumab (Keytruda®, an immunotherapy drug recently approved for use in cervical cancer), but C1/C2 typing will need to be incorporated into clinical trials to test this.”