Adding radiotherapy to the current standard treatment for breast cancer did not improve survival rates for patients aged 65 years or older.

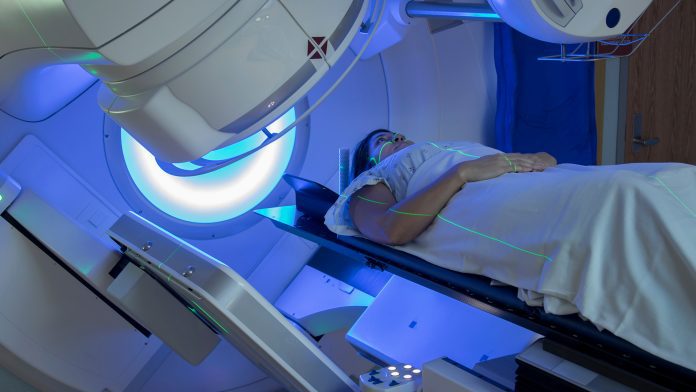

Radiotherapy is a treatment where radiation is used to kill cancer cells. It can be used to try to cure cancer, make other treatments more effective, reduces the risk of cancer returning after surgery, and relieve symptoms if a cure is not possible. It is generally considered the most effective cancer treatment after surgery, but its effectiveness varies between individuals.

A new study by the University of Edinburgh analysed the role of radiotherapy in treating breast cancer, alongside breast-conserving surgery and hormone therapy, in older patients and whether it impacted death rates.

The findings have been published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Conducting a ten-year clinical trial of older breast cancer patients

The ten-year study is one of the first long-term clinical trials in older breast cancer patients. Regardless of age, the standard treatment for early breast cancer is breast-conserving surgery, sometimes called a lumpectomy, followed by radiotherapy and hormone treatment to reduce the risk of recurrence in the breast.

Patients aged over 65 years represent almost 50% of patients with the condition. Despite this large number of affected individuals, there have been few clinical trials addressing this age group.

Is radiotherapy a necessary step?

The researchers conducted a randomised clinical trial called PRIME II that involved 1,326 patients. The aim was to explore if radiotherapy was necessary in combination with a lumpectomy and hormone therapy.

The patients were 65 years of age or older with ‘low-risk’ breast cancer, which means a tumour no more than 3cm in size, not involving the lymph nodes underneath the armpit and likely to respond to hormone treatment.

All the patients had breast-conserving surgery and at least five years of hormone therapy; half of the group were assigned to also have radiotherapy for three to five weeks after surgery. The patients’ progress was assessed at annual clinic visits and with breast scans.

The team found that in patients treated without radiotherapy, the risk of cancer recurrence in the treated breast after ten years was 9.5%. However, when radiotherapy was given, the risk was reduced to 0.9%.

There were no differences recorded in overall survival between both groups, and most deaths were due to causes other than breast cancer.

“Radiotherapy can place a heavy burden on patients, particularly older ones. Our findings will help clinicians guide older patients on whether this particular aspect of early breast cancer treatment can be omitted in a shared decision-making process, which weighs up all the risks and benefits,” commented Professor Ian Kunkler, Professor of Clinical Oncology at the University of Edinburgh.