We are living through a mental health crisis. Existing treatments barely scratch the surface of the problem, and have not translated into real-world benefit for a huge number of people.

By Amanda Feilding

An estimated one billion people worldwide now live with a mental disorder, with depression affecting an estimated 264 million people of all ages around the world. It is the single biggest contributing factor to suicide, responsible globally for an estimated 800,000 deaths every year, and is the second most frequent cause of death among 15- to 29-year-olds. In the UK, 30% of patients find existing therapies to be ineffective, with 1.2 million people suffering from treatment-resistant depression.

Despite the rapidly growing problem, there has, arguably, been little progress in terms of treatment options since 1974, with the discovery of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), such as fluoxetine and citalopram. That is, until now.

Pioneering psychedelic research

It is more than 50 years since I first realised what amazing tools psychedelics can be. In 1965 I was introduced to LSD, and most importantly, in 1966 I met, and became deeply involved with, an exceptional Dutch scientist, called Bart Huges, from whom I learnt two important hypotheses: the first one about the mechanisms underlying altered states of consciousness; and the second, the description of the ego as a conditioned reflex mechanism that controls the distribution of the blood in the brain.

That is when I decided that I had found my ‘mission’ in life – to scientifically research these changing states of consciousness, and their potential value for humanity, and to integrate this knowledge into modern society.

I realised then that the only way to overcome the Taboo surrounding cannabis and psychoactive compounds was with the very best science, as our society has replaced the authority of the spiritual with the supremacy of science.

Thus, in 1998, I founded the Beckley Foundation with the goal of undertaking unimpeachable scientific research into psychedelic compounds, and evaluating their therapeutic benefits for mental health and wellbeing. Over the years, I have undertaken many collaborations with leading scientists around the world. In the UK, my partnership with Professor David Nutt has been particularly rewarding. In 2008, David moved to Imperial College London, and we began the Beckley/Imperial Research Programme, co-directed by David and me, with Robin Carhart-Harris as our Principal Investigator.

While my true passion lay with LSD, David and I decided that decades of poisonous propaganda, plus its unfortunate nickname: ‘Acid’, had made it too taboo in the public (and regulatory) consciousness to work with. With that in mind, we instead decided first to pursue research into its relatively unknown cousin, psilocybin. In 2012, we published the first images of the brain under the influence of psilocybin, obtained with functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI), in healthy participants. Groundbreaking results from this work demonstrated for the first time a decrease in blood supply to regions of the Default-Mode Network (DMN), a network of brain regions involved, among other things, in introspection, narrative identity and thinking about past or future events, and whose hyperactivity had recently been associated with the excessive rumination underlying depression, and other psychological disorders.

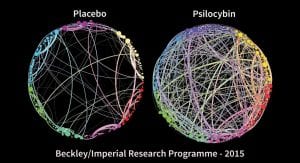

Employing cutting-edge methods of connectivity analysis and graph theory, we found an association between psilocybin-induced ‘ego-dissolution,’ and decreased functional connectivity between regions of the DMN. Our research also revealed how the acute psychedelic state is characterised, neurologically, by a dramatic increase in communication between the different networks of the brain. Connections appear, or are strengthened, between regions that do not normally communicate with each other. This leads to a looser style of cognition, more prone to making new associations, which can facilitate spontaneous self-insight, fresh perspectives, and creativity.

Most importantly, the effects of psychedelics are not limited to the acute experience, but often lead to lasting changes that can transform patterns of thought and behaviour in the long-term. An increase in cognitive flexibility and openness are two key elements in the long-term therapeutic benefits of psychedelics, providing individuals with the ability and willingness to change and adapt, thereby breaking rigid thought patterns that have kept them prisoners of their own mind.

Our early findings with psilocybin presented a breakthrough in our understanding of mental illness and how we might be able to improve the treatment of a variety of associated disorders, all based on psychological rigidity, such as depression, addiction, obsessive-compulsive disorders, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), that blight the lives of millions of people worldwide.

This initial Beckley/Imperial study led to the Medical Research Council, a government body, funding our subsequent feasibility study into using psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy for patients with treatment-resistant depression. This study, when published in 2016, generated a global wave of interest, and paved the way for the clinical development of psychedelic-assisted therapy for the treatment of depression, and eventually the creation of the first psychedelic ‘unicorn’ company (i.e. a company valued at over $1bn).

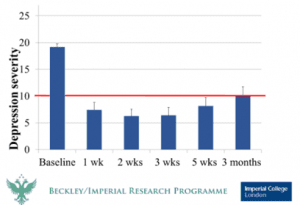

As part of our feasibility study, 20 participants were recruited, all of whom had previously tried at least two other treatment methods without success, and who had suffered from depression ranging from moderate to severe for an average of 18 years. All patients showed some reductions in their depression scores at one-week post-treatment, and these were sustained in the majority for three to five weeks. At five weeks, 21% were in complete remission and 47% of patients had their depression scores reduced by half or more (which is called a ‘clinical response’). Remarkably, results remained positive six months later, with 31% of patients still maintaining clinical response. The drug was also well tolerated by all participants, and no patient except one sought conventional antidepressant treatment within five weeks of the psilocybin intervention.

This feasibility study remains a landmark in the history of psychedelic research and has proven to be extremely influential, confirming, as it did, that psilocybin is safe and largely effective as a treatment for depression in patients who were unable to find relief elsewhere.

In 2019, the team at Imperial College undertook a larger study, which represents the much-anticipated follow-up to our initial 2016 feasibility study, expanding the scope of the research in order to directly compare the efficacy of two psilocybin sessions with that of conventional antidepressant medication – in this case, six weeks of escitalopram – in 59 patients with Major Depression (30 on psilocybin vs 29 on escitalopram). Both groups received similar psychological support.

The results, published recently in the New England Journal of Medicine, show that while depression scores were reduced in both groups (without significant difference), the reductions occurred more quickly in the psilocybin group, and were greater in magnitude, with fewer side effects.

Reflecting the success rates of our earlier study, in this new study, after six weeks and two psilocybin doses, 70% of people in the psilocybin group saw their depression scores reduced by more than half, compared with 48% in the escitalopram group. In addition, remission of symptoms at six weeks was seen in 57% of the psilocybin group, compared with just 28% in the escitalopram group.

However, the main results may, at first glance, be cause for some disappointment. Indeed, both groups showed a similar level of improvement in their depressive symptoms, as measured with the QIDS-SR-16 depression scale. But this lack of significant difference should not be interpreted as a lack of advantages of psilocybin over traditional antidepressants. It must indeed be kept in mind that the psilocybin group only received two doses of 25mg, whereas the other group received 63 doses of 10mg of escitalopram, and experienced many more side effects.

It is also worth noting that in this study, both groups benefited from extensive psychotherapeutic support, which is not normally the standard of care for depressive patients on SSRIs.

These results undeniably confirm the benefits and safety of psychedelic-assisted therapy, and now an issue of primary importance is how best to begin providing access to these therapies to those in need.

At the same time, of course, we need to reform our outdated regulatory system, and to reschedule psychedelics to a lower level of restriction, which recognises their medical potential, and permits doctors to prescribe them where appropriate.

Next step: the provision of access

As a growing number of studies, whether clinical or observational, collectively demonstrate the safety and efficacy of psychedelics in helping manage multiple mental health conditions, many people in need are now seeking access to these treatments. The Beckley Foundation regularly receives emails and phone calls from individuals desperate to get access to psychedelic-assisted therapy. They have often tried everything and the little hope they have left lies in the therapeutic promise that this new approach may afford. Unfortunately, at the moment, we cannot provide any form of guidance; but it feels utterly wrong that these people are left so hopeless, while we know that psychedelic-assisted therapy’s potential benefits, in all likelihood, far outweigh its risks. For these individuals to gain access to psilocybin, they are therefore forced to either break the law, or travel abroad to places like the Netherlands.

Thus, the next major problem which needs solving is the provision of safe, legal, and affordable access to high-quality psychedelic-assisted therapy.

My aim when I established the Beckley Foundation was two-fold: to carry out the best research in order to explore and expand our understanding of psychedelics; and to get psychedelic compounds rescheduled and legally available to those in need.

It was, and indeed is, my belief that these two aims can work in synergy, with research informing policy reform, which in turn facilitates more research, and in time leads to expanded access. This has proven to be the case, as positive findings from research into psychedelic-assisted therapy for depression, and other conditions, have led to a greater movement towards providing access, including grassroots-led campaigns for reform across North America, and more recently Australia. Colorado was the first city to decriminalise psilocybin in 2019, followed soon after by municipalities in California and Massachusetts. I was also glad to be an early supporter of the successful ballot initiative in Oregon (which I discuss in more detail below). Meanwhile, in Canada and Switzerland, exemptions from drug regulations have been granted to certain individuals suffering from depression and end-of-life distress, allowing them to legally receive psychedelic-assisted therapy (although, it must be said, for the vast majority of those in need, these efficacious treatments are still not available).

In 2016, I presented at the UN in New York a Beckley Public Letter calling for the abandonment of the 1961 Drug Convention, and for every country to be permitted to implement the drug policies which their governments consider best for their citizens: policies that are effective, harm-reductive, and respect human rights. This obviously requires the rescheduling of certain psychoactive compounds which were originally mis-scheduled due to ignorance, or political expediency.

Perhaps the most notable recent drug policy reform success has come in the US state of Oregon, which became the first state to decriminalise psilocybin and legalise it for medical use, after Measure 109 was passed in November 2020, with the approval of 55.75% of voters. In addition to decriminalising and legalising, it specifies a number of provisions aimed at ensuring competency of facilitators, appropriate screening of patients, adequate preparation and integration for participants, and a high quality of medicine. It is also intended to open up psilocybin therapy to all adults who can safely benefit, not merely those suffering from treatment-resistant depression.

I, and many others, will be watching with interest to see whether or not Measure 109’s proposed model is a success. If it is, it could provide inspiration for subsequent legislation and regulation around the world.

Currently, the establishment of clinics, retreat centres, and certified lists of therapists, which could provide the psychedelic-assisted therapy for those in need, is blocked by the current scheduling of psychedelics as Schedule 1 (indicating no medical benefits, the highest level of potential harms, and therefore the highest category of restriction). However, it is ever clearer, as study after study has shown, that these compounds are low in harms and high in potential benefits.

The time for change is long overdue.

The Medical-Pharma approach

The global move to develop this therapy as a new, more efficacious treatment for many mental health disorders such as depression, anxiety, addiction, PTSD, among others, was initially based on research motivated by a handful of passionate, non-profit-motivated pioneers.

However, what started as a purely philanthropically-funded field of research is now attracting a new wave of interest from investors, as the winds of the cannabis goldrush blow over to psychedelics, which are becoming the latest darlings of the pharmaceutical investor.

Lessons must be learnt from some of the failures of the cannabis movement, and while there is most certainly a place for for-profit investment in this new sector – as the costs of clinical trials and scalable care-delivery, not to mention the social and political pressure needed to bring about policy reform, will most likely be beyond the resources available to the non-profit sector on its own – I am mindful of the risks that come hand in hand with this new type of money: the need to satisfy the ‘hunger’ of some investors, the willingness of some to cut corners, the competitive spirit overwhelming the sense of co-operation and collaboration, plus the temptation to hoard intellectual property, and claim exclusive private ownership over what rightfully belongs to the commons, thereby depriving the patient of the treatments they desperately need. These are all very real risks, each of which could set back the Psychedelic Renaissance, which I and many others have spent so long labouring for.

We must encourage conscientious and responsible investors, together with mission-aligned entrepreneurs, so that ethical principles of reciprocity, stewardship, equitable access, and putting the good of society above maximum profit, are the cornerstones of psychedelic businesses.

It is with these values in mind, that since 2019 I have co-founded two new Beckley organisations, in order to help carry out my long-held mission of integrating these amazing compounds into the fabric of society. I realised that the modest, non-profit philanthropic donations that funded the Beckley Foundation were insufficient to bring about the radical changes needed in order to make these compounds legally regulated and widely available to those in need.

The first is Beckley Psytech, which is a drug development company, committed to putting patients first, and focused on taking various psychedelic compounds through clinical trials so that they can become regulated pharmaceutical medicines to treat various neurological and psychiatric disorders. The second is Beckley Waves, which is a venture studio that will build and invest in startups devoted to expanding safe, legal, and affordable access to psychedelic-assisted therapies and other altered states of consciousness that can improve mental health and wellbeing.

These new companies will complement the vital non-profit work that I will continue to lead on at the Beckley Foundation.

However, despite the influx of for-profit money and skills into the psychedelic field, there is still a vast amount that must be done by the non-profit sector, especially in terms of the most cutting-edge and exploratory scientific research, particularly in those cases where there is little or no profit potential.

Indeed, just as this new for-profit ecosystem has been built on the foundations laid by non-profit research done by institutions such as the Beckley Foundation, MAPS, Heffter, Imperial College, Johns Hopkins, and others, so I am sure that many of its future areas of opportunity will also be based on the breakthrough studies of these same non-profit organisations.

For this reason, it is critical that we do not forget the great need for continued philanthropy in this sphere.

The new challenge for philanthropy is that their goodwill can be undermined by the fact that, next door to them, the investor is investing similar money with the potential of high return, and thus the philanthropists rightly have the sense that the fruits of their non-profit contribution are maybe helping provide profit to the investor. This thought can understandably be putting off for some philanthropists, thereby making the raising of philanthropic donations even more difficult.

Nevertheless, without the support of generous private donors and institutional funders, the essential work of non-profit psychedelic organisations, which continue to push the limits of our knowledge by conducting the best possible independent research and dare to explore new and taboo territories without consideration of profit, would not be possible.

For more info or to support the Beckley Foundation’s Research, visit: www.beckleyfoundation.org/

Amanda Feilding

The Beckley Foundation