Sepsis Alliance Board member Dr Cindy Hou speaks to Health Europa Quarterly to discuss the burden and prevention of sepsis.

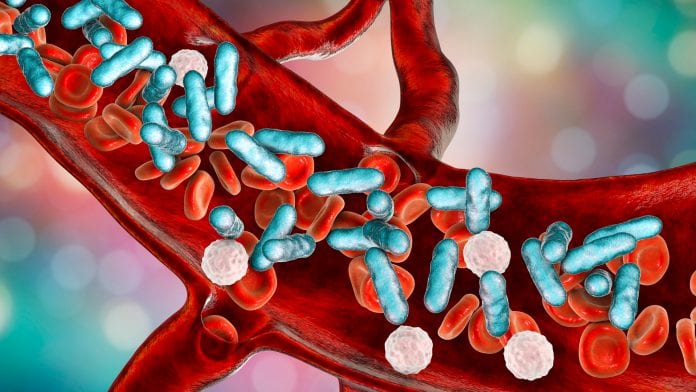

Sepsis occurs when the immune system overreacts to an infection and begins attacking the body’s own cells. It is fatal in 30% of severe cases and accounted for almost 20% of global deaths in 2017. Dr Cindy Hou of the Sepsis Alliance’s Board of Directors tells HEQ about the burden and prevention of sepsis.

How did the Sepsis Alliance come to be founded? What are the Alliance’s key aims?

The Sepsis Alliance was established in 2007 by a dentist named Dr Carl Flatley. His daughter, who was an aspiring teacher, went in for surgery and died unnecessarily of sepsis at the age of 23. Dr Flatley went looking for information about sepsis and learned that no organisation existed yet, so he founded the Sepsis Alliance to improve the public’s knowledge about the risks and prevention of sepsis – later on, the organisation would expand its focus to deliver sepsis education to healthcare providers, in an effort to reduce morbidity and mortality from sepsis. Sepsis awareness can and does save lives, yet only 71% of US adults recognise the word ‘sepsis’ – although this is up from 19% at Sepsis Alliance’s founding.

The mission of Sepsis Alliance is to save lives and reduce suffering by improving sepsis awareness and care. The Sepsis Alliance team is working on producing as much information and educational material as possible to help the general public become aware of this often deadly condition, and for professionals who can then help the public learn about sepsis when it does strike. Along the way, in addition to creating education for healthcare providers and the public, the Alliance has branched out into a number of different arms: there is a website aimed at the clinical community, which provides educational modules for sepsis co-ordinators and healthcare providers; there is an arm called the Sepsis Alliance Institute which delivers education across the continuum of care; there is another separate branch called the National Sepsis Registry Initiative (NSRI), which was established with the ambitious goal of creating a national sepsis registry for the USA. There are many different themes of the Sepsis Alliance, but what they all boil down to is education and improving awareness of sepsis, because that is how you save lives.

How common are hospital-acquired infections (HAIs)? Are there any significant risk factors or particularly vulnerable demographics?

HAIs are unfortunately still quite common. However, healthcare providers in the United States are making inroads in terms of reducing some of the more commonly known HAIs; and a large part of that is due to the adoption of a bundled checklist approach, much like when a pilot gets on a plane and there are certain things they have to do before they start the engines. All of that is very evidence-based and multidisciplinary, so it is not just reliant on physicians, but also nurses; and increasingly we need to engage patients, because they need to be made aware of the risks and benefits of different items. For example, significant inroads have been made in terms of reducing central line-associated bloodstream infections (CLABSI) – one of the keys for preventing an infection is to have an awareness of all these different devices that we use, especially with the critically ill patients who have the misfortune of going into the intensive care unit.

It is essential to look at ways to prevent the risk of contamination both before and after those devices are introduced into the care pathway, and everything is handled correctly that can certainly prevent infections. We are making inroads, but there are definitely still more opportunities for improvement; and from a worldwide perspective, there are also significant disparities in HAI incidence and treatment between developed and developing countries.

Populations which are particularly vulnerable to infection would include the very young and the very old, as well as those who have comorbidities which could make them potentially more susceptible to infection. For example, patients may be immunocompromised because they have cancer and they need chemotherapy, or if they have an autoimmune disease and have to take medication that suppresses their immune system; and even if a patient is not on any of those immunosuppressive treatments, if they are elderly, their immune system may behave differently.

Patients are also especially vulnerable if they go to the intensive care unit, because that means that they will be more likely to need some sort of foreign device: introducing any device into the body that we are not born with heightens the risk for infection, but if the device is properly maintained and the correct steps are taken to prevent infection before it is put in, it should be possible to prevent all of the downstream sequelae. We need to pay attention, not just in intensive care or even in the hospital setting, but across the continuum of care – whether a patient goes into a nursing home or they are at home, if they have these foreign devices in place out of necessity, there are still ways to prevent infection.

What actions can clinical and care facilities take to minimise the risk of patients and staff contracting or spreading infections?

There is definitely a role for patient education, not just in terms of encouraging the patient to come to the facility, but also in the form of community outreach. Ongoing education is also important to nursing staff and physicians, but there are certain things which do need to be hardwired. For example, a peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) is an intravenous (IV) line that goes into the arm; and it is quite invasive, so if the patient does not specifically need the PICC line or they need something that is less invasive, there are short-term IV catheters or smaller IVs: everything is focused around looking backwards through a sequence to determine whether the least invasive approach is possible. This approach is partly the result of the research and knowledge of technology that clinical providers have amassed over the years, which have allowed them to develop different alternatives.

One of the key aspects of infection prevention is establishing, even before a device is introduced into the treatment pathway, whether it is absolutely necessary or whether there is an alternative non-invasive route – with Foley catheters, for instance, there is a great risk for infection; and so there are now alternative means available to capture urine output without having to put in a Foley catheter, so they would typically be preferable from an infection prevention standpoint. Sometimes a foreign device is needed, but then every day we have to question whether it is still necessary, because prompt device removal also helps to prevent infection.

In addition to education and research, there is certainly a role for technology in infection control; but a lot of infection control as a whole comes down to prevention. Many of these prevention measures have become more popularised as a result of COVID-19, such as hand hygiene and taking steps to protect our environment from contamination.

What are the key challenges currently facing the management and treatment of HAIs?

One of the major challenges which occur is when HAIs happen to be multidrug-resistant, because then patients may suffer from further complications, so they remain in the hospital longer; and the longer they stay the weaker they get, so then once they leave hospital, they will have to go to a rehabilitation centre to recuperate before they can go home. All of that presents challenges both from the patient perspective and from the management perspective. Sometimes the treatment provider will have to optimise the antibiotic or determine whether a fungal infection is present, so it is essential to ensure that the knowledge is there to properly treat the infection, as well as to find and address the source of infection – for example, if the infection was initially caused by a Foley catheter, it would be necessary to readdress whether that catheter could be removed to prevent further complications.

What is post-sepsis syndrome?

Post-sepsis syndrome can take place in people who have suffered from sepsis; some estimates indicate that up to 50% of people with sepsis can have symptoms well after the infection itself has been treated. Symptoms could be physical or psychological or both. Some people have fatigue, weakness or tiredness; they may be short of breath or just feel debilitated. They can suffer from a degree of trauma from a psychological standpoint, and go on to suffer from depression or anxiety.

A lot more attention needs to be focused on this issue; and this is one of the key reasons why we really need a continuum of care, focused around observing the journey of patient once they go from the community to the hospital and back, and ideally well beyond that. The other issue is that, while post-sepsis syndrome is the terminology, it is not officially recognised as a distinct condition – which is a shame, because a lot of people are suffering from it and so we need to increase awareness so that the needs of this gigantic population of people can be properly addressed.

Some experts have theorised that long COVID may be related to post-sepsis syndrome – is this feasible?

There are certainly similarities between the two. People who have COVID-19 can experience different degrees of symptoms – they could be asymptomatic, they could have mild symptoms or they might have severe symptoms – so a patient with COVID-19 could have viral sepsis and after they have recovered from the acute illness, they could have post-sepsis symptoms. There are still differences between post-sepsis syndrome and long COVID, because post-sepsis symptoms can arise from an array of sources, whether the initial infection is bacterial, viral or fungal. However, there is a lot of overlap; when we talk to survivors of sepsis, they hear about long COVID and say that it is essentially what they had. In a sense, long COVID has helped to increase awareness of sepsis and post-sepsis syndrome.

Dr Cindy Hou

Board of Directors

Sepsis Alliance

www.sepsis.org

This article is from issue 17 of Health Europa. Click here to get your free subscription today.