Inflammatix spoke with Andy Breakell, an emergency medicine consultant at the Royal Liverpool Hospital and Tony Cambridge, lead biomedical scientist at Plymouth Hospital about point-of-care testing and how this can be applied in A&E.

Learning from the first four waves of COVID-19

The first four waves of the COVID-19 pandemic have placed an enormous strain on hospital accident & emergency departments (A&E) as much as anywhere in the UK National Health Service. This period has also seen great innovation and learning, with the introduction of new patient pathways and novel diagnostic technologies to help enable them. Today, the service remains under huge pressure from a lack of hospital and community capacity to allow for flow through the A&E, rising attendance rates, an ageing population, and staff shortages. Recent reports indicate that up to one in three hospital beds are occupied by patients who are medically fit for discharge.[1] With winter upon us, we can expect further pressure from industrial action and both seasonal flu and another increase in COVID cases.

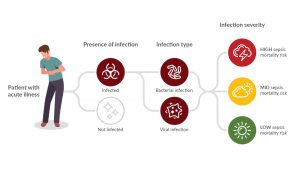

Inflammatix, Inc. is developing an innovative point-of-care platform and a test to aid in the diagnosis of acute infection and sepsis. [2] Their TriVerity™ Acute Infection and Sepsis Test in development will measure 29 genes from whole blood to detect the immune response to infection, irrespective of the location or source of the infection [3]. Their point of care platform then applies a unique, fixed, machine-learning classifier to measure the genes to provide the likelihood of:

- bacterial infection,

- viral infection,

- Severe illness, requiring critical care, within the next seven days.

Necessity is the mother of invention; how has your triage and A&E diagnostics been changed by the first four waves of the COVID-19 pandemic?

AB: We brought rapid diagnostics right to the front door of the A&E using lateral flow (LF) tests at triage. They were fast, cheap, and fitted the need at that point in the pathway. It allowed for rapid differentiation between infectious and potentially non-infectious patients. We then had time to confirm with a more reliable molecular point-of-care test, deeper in the department. It was all about finding the right tool for where you were in the care pathway.

TC: In Plymouth, point-of-care molecular testing was done in the A&E by staff at the height of the waves to streamline triage. This testing was moved back to the lab when there were fewer cases presenting. The A&E recognised this need too and allocated a budget for microbiology to employ technicians to cover point-of-care testing. However, this came a little late, after the worst of the fourth wave. During the pandemic, A&E staff ran tests on a small point-of-care molecular device in a side room and other POC devices across the department.

What were the key learnings from the first four waves in terms of what is possible and what is practical from point-of-care testing?

TC: Look after the staff! Of the six technicians we employed, some left for other roles. We have managed to recruit two more to support both lab and point-of-care testing. If the approach is to have a long-term future we need to ensure the role is defined and expectations communicated at the recruitment stage.

AB: That’s the danger of not having the A&E staff running the tests. If the techs leave, the A&E staff do not know how to use the kit and the service suffers. Nurses do the testing at the Royal Liverpool Hospital. The redesigned workflow of separating the infectious from potentially non-infectious patients was made possible by point-of-care testing. The key was understanding the need at each stage of the care pathway and applying the test that could help to move it along.

TC: Point of care deployed well can accelerate determining which pathway patients should be on and then accelerate their journey along this care pathway. Point-of-care innovations can promote new ways of delivering healthcare. Any new solution requires expert clinical input to ensure the tests are deployed appropriately for the maximum effect on patient management.

What remain the biggest challenges and unmet needs with the diagnosis of acute infection and sepsis in the A&E?

AB: Test turnaround time is critical. We book in 20-30 patients an hour so long turnaround times mean backlogs and delays in decisions. We no longer have the LF tests in the A&E so we have lost control of those with positive Covid tests. There is a higher risk than 12 months ago for viral transmission now the provisions that were in place at the height of the first four waves have been relaxed.

TC: We do not have a hot lab or STAT lab in the A&E but may have to look at this as models of pathology provision are changing rapidly. If there is another surge, how prepared are we to escalate back to where we were? Probably not as able as we might be.

AB: Chest infection with bacterial pneumonia is a common presentation to A&E. Those with infections for four to five days may be less contagious as the infection may be deep in lung tissues. Those with COPD may have mixed viral and bacterial infections. There are currently no specific biomarkers for bacterial sepsis validated by peer review research. The current combination at A&E triage is a) Patient appearance, b) Vital signs (NEWS2 score) and c) the biomarker C-reactive protein (CRP). We use the Sepsis 3 guidelines (Glasgow Coma Score, Respiratory Rate and Systolic Blood Pressure) together with NEWS2 and CRP to direct our decision to prescribe immediate antibiotics.

What impact are you looking for in new point-of-care testing?

AB: It would have to help accelerate the decision-making process and add a greater level of certainty which would be reflected in specificity. We already know that CRP above 20mg/L is sensitive to all-cause infection, but not very specific. Cultures are too slow for A&E. CRP is our most widely researched biomarker and the one for which we have the most knowledge. All infection begins with inflammation but not all inflammation means infection. This means there is an overlap of immune response with humoral and cell-based factors at play. Any test would also need to cover the “illness timescales” which for infection could be the first six hours or ongoing for days with test results elevated on day one, changing over time.

Based on the challenges with current diagnostic tests for acute infection and sepsis that you described before; do you think that a host immune response-based point-of-care testing could work in the A&E?

TC: With new technology, there is always an element of faith. Even if the test concept makes sense, it can be tricky to change methodologies. It all comes down to the evidence you can present. Evidence of performance. Evidence of utility and of course value for money.

AB: It would have to demonstrate that it was better than the current standard of testing for infection as described above with a mix of clinical assessment, vital sign scores and the biomarker CRP. A rapid result is important due to patient volumes, and it would need to show superiority to those biomarkers we understand e.g. CRP and the newer biomarkers like Interleukin 6 and PCT. We know that different levels of CRP are associated with the type of infection and possible prognosis depending on the time from infection onset and level. I use CRP in the A&E department to gauge risk after the clinical assessment, but like everything in medicine they are not watertight “rules”.

Is the NHS in a position to adopt novel technologies, especially in the A&E?

TC: If the test could demonstrate performance superior to current best practices and impact key indicators, there is always an appetite to innovate. The A&E is critical and under pressure. Technologies that can be shown to accelerate or change a pathway should be considered, as flagging the high-risk patients in a crowded A&E department, literally packed, is really hard.

AB: I am not a fan of the length of stay as a measure of good clinical practice when researching point of care. Finding the sickest in a crowded department is a better measure. Any test that flags up those at high risk, in my book, is a valid piece of kit. You may identify a urine infection within five minutes, but if the wait to see a doctor is 12 hours, you’ll still wait 12 hours. The troponin cardiac biomarker is a good example of this high-risk biomarker that promotes early treatment even with long inpatient bed delays. A measure of severity is interesting. Having information about a relatively well-looking patient that may have some underlying high-risk condition, maybe acute abdominal infection e.g. appendicitis would be a great asset as a point of care device and if that kit signals a severity score of e.g. four out of five for high-risk necrosis, then that’s a massive bonus. If point-of-care testing can do all that, it would be a credit to the researchers and manufacturers.

Inflammatix, Inc. has partnered with Pro-Lab Diagnostics to bring our ground-breaking new test, to clinicians in the UK first upon receipt of the UKCA mark.

To learn more about our innovative immune response approach you can visit us at Inflammatix.com and follow us on Twitter @Inflammatix_Inc and LinkedIn (Inflammatix, Inc).

[1] NHS England, https://www.england.nhs.uk/2022/11/hundreds-of-beds-taken-up-by-flu-patients-every-day-ahead-of-winter/ accessed 6th December, 2022

[2] Features may change during the development process. Products in development, are not for sale and do not have marketing approval or clearance from regulatory authorities in any jurisdiction.

[3] The optimization and biological significance of a 29-host-immune-mRNA panel for the diagnosis of acute infections and sepsis. He et al. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 2021