For the first time, scientists have uncovered a disease mechanism whereby fat crystals cause chronic inflammation of the immune system.

Scientists at the University of Bonn have shown that a congenital disorder of fat metabolism can apparently cause chronic inflammation and hyperreaction of the immune system. Some individuals suffer from a rare genetic defect that causes their cells to form an unusual kind of fat, the consequences of which can be grave. In some patients, the nerve cells responsible for transmitting pain die over time; others lose their hearing or suffer early-onset dementia. Another frequent symptom is skin defects that only heal with great difficulty, which can even become chronic.

The results are published in the journal Autophagy.

Understanding the genetic mutation

It has been known for several years that the underlying mutations alter an important enzyme in the fat metabolism, which normally produces a certain type of fat. Due to the mutations, however, it now uses the wrong building block which causes large quantities of so-called ‘deoxysphingolipids’ to be produced in the body’s cells – around ten times more than normal.

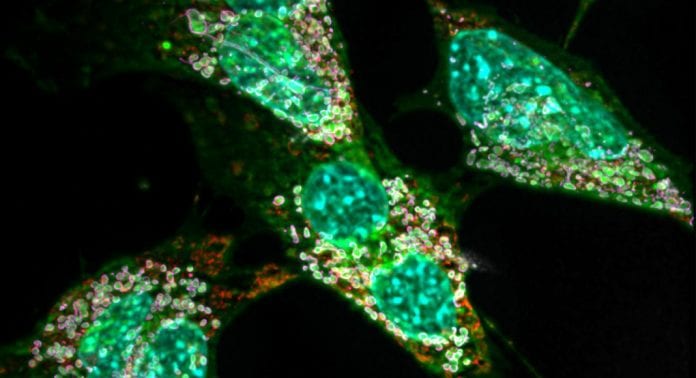

Dr Lars Kürschner from the LIMES Institute at the University of Bonn, said: “These exotic molecules have the disadvantage that they can only be degraded very slowly. In high concentrations they also form crystal-like lumps in the affected cells.”

The fat crystals massively disrupt the function of the cell’s internal powerhouses known as the mitochondria. Particularly cell types with a high energy requirement can suffer so much that they perish. “This mainly affects the nerve cells,” says Kürschner. “This is also the reason for the impaired pain transmission and other neurological symptoms.”

The researchers have been able to detect such mitochondrial defects in connective tissue cells of mice and were also able to track down another effect thanks to preliminary work by colleagues in Bonn. In this work, immunologist Dr Eicke Latz from the University Hospital in Bonn showed that cholesterol crystals can cause inflammatory reactions. Cholesterol is also a fat. “We therefore wanted to find out whether the deoxysphingolipid crystals also have an effect on the immune system,” explains Kürschner.

Chronic inflammation

The researchers examined certain immune cells of the mouse, the macrophages, which act as the body’s own garbage collection system. In the course of disease, macrophages, like nerve or connective tissue cells, also produce large amounts of deoxysphingolipids and absorb the abnormal fats of dead cells in their capacity as garbage trucks. In other words, they get twice the dose of fat crystals.

This process massively disrupts the function of various cell components, such as the mitochondria, in these macrophages (as in neurons and other cells). They respond by dismantling the damaged powerhouses in order to produce new mitochondria from their components – a mechanism known as autophagy.

“Nerve cells and connective tissue cells also do this,” says Mario Lauterbach, lead author of the study. “However, macrophages are immune cells; this means that they have additional options for perceiving damage and reacting to it. One of them is that in autophagy they activate a molecular complex that promotes inflammation, known as the inflammasome.” The activated inflammasome in turn causes the macrophage to release inflammatory messengers. In this way it calls on other immune cells for help, including other macrophages, which further intensify this effect.

“One consequence of the accumulation of these abnormal fats is therefore a manifesting inflammation,” explains Lauterbach. This may be responsible for the poorly healing wounds observed in many patients.

Is treatment possible?

The researchers now hope that these symptoms can be treated with drugs that inhibit autophagy. “There are already some candidates that are currently being tested,” says Kürschner.

The results could also shed new light on a much more common condition: diabetes, a disease in which physicians regularly observe severe chronic inflammation, which contributes to the serious effects of the disease. In diabetes patients, deoxysphingolipid production is also increased in some cells and the cause is still largely unknown.