Researchers tested chemical compounds for their ability to inhibit malaria parasites at earlier stages & may have stumbled on new malaria prevention drugs.

Chemical starting points for new malaria preventatives have been revealed, according to the research team at the University of California San Diego School of Medicine, USA. This ground-breaking research could lead to new malaria prevention drugs to be developed.

What was done differently?

The research team targeted the malaria parasite at an earlier stage in its lifecycle, when it initially infects the human liver, rather than looking at ways of tackling the disease after it has been diagnosed.

The team spent two years extracting malaria parasites from hundreds of thousands of mosquitoes and using robotic technology to systematically test more than 500,000 chemical compounds for their ability to halt the malaria parasite at the liver stage. After further testing, they narrowed the list to 631 promising compounds that could form the basis for new malaria prevention drugs.

Moreover, to help speed this effort, the researchers made the findings open source, meaning the data is freely shared with the scientific community.

Elizabeth Winzeler, PhD, professor of pharmacology and drug discovery at University of California San Diego School of Medicine, explains: “It’s our hope that, since we’re not patenting these compounds, many other researchers around the world will take this information and use it in their own labs and countries to drive antimalarial drug development forward.”

The road to malaria prevention drugs

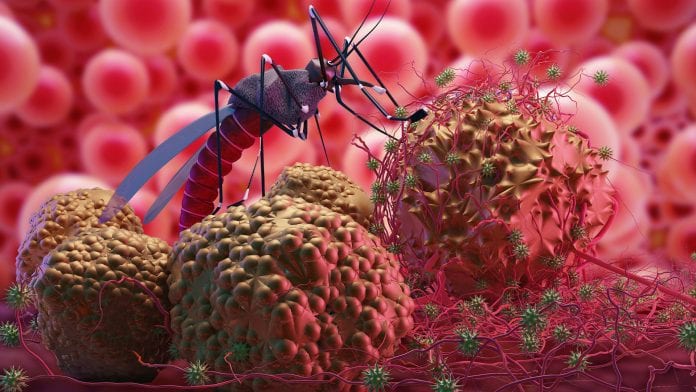

Most cases of malaria are caused by the mosquito-borne parasites Plasmodium falciparum or Plasmodium vivax. This parasite begins its lifecyle when an infected mosquito transmits sporozoites into a person while taking a blood meal. A few of these sporozoites may establish an infection in the liver and after replicating there, the parasites burst out and infect red blood cells, which is when an individual experience the typical malarial symptoms.

The team aims to take a closer look at the 631 promising drug candidates to determine how many of them work against the liver stage of the Plasmodium species that affect humans. Winzeler and members of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation Malaria Drug Accelerator (MalDA), an international consortium focused on speeding drug development, are working together to unravel the mechanism by which many of the compounds work against malaria and look towards developing malaria prevention drugs.

The team and others will also continue the work necessary to develop malaria prevention drugs that are safe for human consumption and effective at preventing liver-stage parasites from replicating and bursting out into the bloodstream. The ideal new drug would also be affordable and practical for administration in parts of the world without refrigeration or an abundance of health care providers.

“It’s difficult for many people to consistently sleep under mosquito nets or take a daily pill,” Winzeler said. “We’ve developed many other options for things like birth control. Why not malaria? The malaria research community has always been particularly collaborative and willing to share data and resources, and that makes me optimistic that we’ll soon get there too.”