Royal Osteoporosis Society Director of Clinical Services Lauren Wiggins tells HEQ about osteoporosis risk, research, and care.

Osteoporosis, which causes the bones to become progressively more fragile and affects more than 3.5 million people in the UK, with millions more at risk of developing the disease. In the EU, approximately 3% of total healthcare costs are directed towards the treatment and care of people who have suffered osteoporosis-related fragility fractures.

The Royal Osteoporosis Society (ROS) is the UK’s only national charity dedicated to bone health and osteoporosis. It works to improve the bone health of the nation and provide anyone living with osteoporosis with support and advice, as well as shaping policy and practice through its work with healthcare professionals and policymakers.

In 2021, it launched its Research Roadmap, with the aim of driving research and developments to work towards a future without osteoporosis.

ROS Director of Clinical Services Lauren Wiggins tells HEQ about the most pressing risks of osteoporosis and new developments in research and treatment.

How common is osteoporosis?

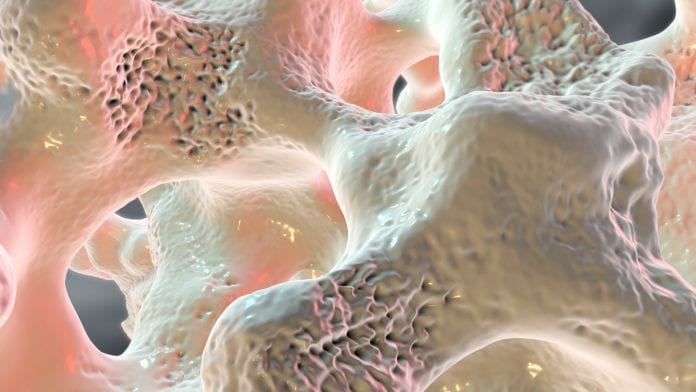

Osteoporosis is a condition that causes bones to lose strength and break more easily. It occurs when the structure inside our bones gets thinner, making them fragile and more likely to break easily. In the UK, half of women and 20% of men over 50 will break a bone because of osteoporosis; and global estimates show figures similar to this.

Although it can affect the whole skeleton, osteoporosis most commonly causes broken bones in the wrist, spine and hip. These broken bones – also known as fractures – not only cause severe pain and significant short-term impact on quality of life, but can sometimes result in life-changing, long-term disability and loss of independence.

Are there any significant risk factors or particularly vulnerable people?

Our bones are alive and constantly changing. Bone mass continues to increase slowly into our mid-twenties. After middle age (35-55), bone loss increases as part of the natural ageing process. This can lead to osteoporosis.

Aside from ageing, some of the most common factors that increase a person’s risk of osteoporosis and fractures include a close family history of osteoporosis; early menopause before the age of 45 years; use of corticosteroids; or some breast cancer treatments. Lifestyle also plays an important role in maintaining good bone health.

When women go through the menopause, their oestrogen levels drop rapidly and their bones lose strength at a much faster rate. This is why women are more likely than men to experience osteoporosis after the age of 50.

Osteoporosis itself does not have any ‘symptoms’ – other than the bones that are broken as a result of the condition. An easily broken bone after a minor bump or fall is often the first sign that our bones have lost strength.

It is a common misunderstanding that osteoporosis causes aches and pains, but the condition itself does not cause pain – although breaking a bone can be painful. This is why osteoporosis is sometimes called a ‘silent’ disease.

What are the key goals of the Research Roadmap?

The Royal Osteoporosis Society launched the Osteoporosis and Bone Research Academy in 2019 to bring together the expertise from the UK and across the world working in the field of osteoporosis. It is a collaborative venture with patients at its heart – together, leading researchers, clinicians, academics, and patient advocates are working to advance scientific knowledge towards a cure for osteoporosis.

During the pandemic, the benefits of collaboration on research could not have been made clearer. The speed of vaccine development for COVID-19 shows what can be achieved when clinicians, academia, government and the private sector join forces in the public interest. These developments inspire hope that other conditions, such as osteoporosis, can be eased or even cured through co-ordinated research.

The Osteoporosis and Bone Research Academy launched its Research Roadmap to experts in the field in December 2020. The aim of the Research Roadmap is to identify the key research priorities which will help bridge the gaps in knowledge on the causes of osteoporosis; novel technologies to assess bone health; and new methods of identifying and treating people who are at higher risk.

The Academy has identified key areas in research and clinical care across three phases of the life course: early growth through development in the womb and during childhood until peak bone mass is achieved in young adulthood; maintenance of bone mass through adulthood; and minimisation of bone loss and fracture risk in older age.

Can you tell me about some of the research projects the ROS has given its backing to?

The ROS offers research grants to support the brightest minds in research and enhance knowledge about osteoporosis. This gives researchers the opportunity to apply for funding for studies that will bring us closer to a future without osteoporosis.

For example, a recent study by researchers at the University of Bristol found that when people break their hip, those living with deprivation stay in hospital longest and are more likely to die. This study has highlighted the need for greater focus on preventing hip fractures in those who experience greater levels of deprivation.

A study currently in progress by researchers at Guys and St Thomas NHS Trust is investigating whether adding vitamin K to the standard treatment for post-menopausal osteoporosis has further beneficial effects on bone density, hip strength and bone turnover.

Another study, by researchers at the University of Surrey, is investigating whether human bone has a ‘bone clock’, regulating how much bone is broken down and formed at any one time of day, thus influencing bone strength and risk of bone fracture. The potential discovery of this ‘bone clock’ is important because it would enable future research into how this clock functions and spearhead the design of new drugs to tackle osteoporosis. Recent discoveries concerning body clocks in human joints has led to funding for the investigative development of new drugs to tackle arthritis and this could also be achieved for osteoporosis.

Building on the previous success of our research grants programme, the ROS is now looking to fund research grants aligned to the key research priorities set out in the Research Roadmap.

How could healthcare policy and practice evolve to better alleviate the burden of osteoporosis?

Osteoporotic bone fractures create an enormous burden on health and social services globally, with a predicted yearly cost of £4.5bn to the UK alone.

Fracture Liaison Services (FLSs) routinely assess everyone aged 50 and over who have broken a bone, to discover whether they have osteoporosis and begin them on a personalised management plan to reduce their risk of further broken bones. These FLSs are an essential part of preventing fractures and reducing healthcare costs. Many people have access to an FLS in hospitals across the UK, and in many other countries worldwide; however in England and Wales the proportions of people able to access an FLS are only 57% and 72% respectively, compared to 100% in Scotland and Northern Ireland.

If everyone over the age of 50 in the UK had access to a good quality FLS, nearly 6,000 broken bones caused by osteoporosis could be prevented every year. As well as protecting people from the pain and debilitation caused by these broken bones, this could save health and care services nearly £66m each year.

Everyone presenting with low-trauma fractures should be assessed for osteoporosis and have a fracture risk assessment as a matter of course to prevent further fractures.

Are there any notable developments or current issues in osteoporosis research or treatment which you would like to highlight?

Despite significant advances in osteoporosis research that have led to real improvements in people’s lives, there are still considerable challenges.

Romosozumab is the first new medication for osteoporosis in a decade. It is currently going through approval processes in some countries, such as England and Wales.

There is an urgent need to intensify the search for answers to beat this cruel disease, and lead to advances in drug treatments to prevent future generations from suffering the devastating consequences of broken bones.

For more information on osteoporosis visit theros.org.uk.

Lauren Wiggins

Director of Clinical Services

Royal Osteoporosis Society

theros.org.uk

This article is from issue 18 of Health Europa. Click here to get your free subscription today.