Two recent studies have highlighted the need for greater ethnic diversity in genomic prostate cancer data and accessible genetic testing.

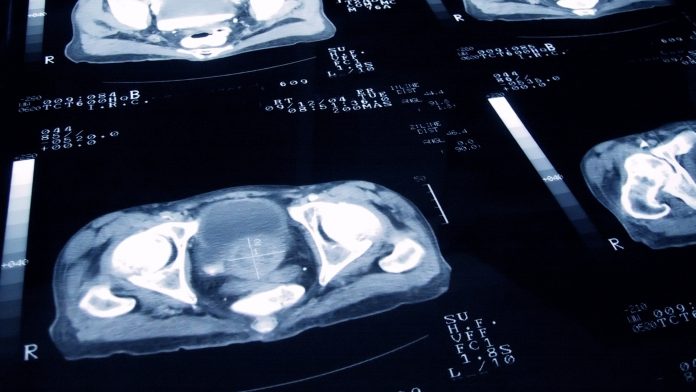

Over 1.4 million men were diagnosed with prostate cancer in 2020 globally, however, the molecular characteristics of the disease remain unexplored for most patients due to limited ethnic diversity in clinical trials.

Scientists have previously established that prostate cancer is a BRCA-gene-associated malignancy. It is understood that prostate cancer develops as a result of hereditary cancer syndrome. It is also understood that men of certain ethnicities can have a predisposition to the disease, with men of African and Caribbean descent at the greatest risk.

Ethnic diversity is key to understanding the roots of cancer

The role of ancestry on the somatic mutations arising in cancer tumours is only now starting to be understood by scientists. This is largely due to both genetic and non-genetic societal-environmental factors linked to ethnicity.

“Such race-related differences can condition the behaviour of the disease and its treatment, yet our current knowledge of prostate cancer genomics is largely limited to data from Europe and the USA, in which Asian and other non-Caucasian ethnicities are scarcely represented,” said Dr Rodrigo Dienstmann, of the Vall d’Hebron Institute of Oncology, Barcelona, Spain.

One study has confirmed the existence of variations in the genomic landscape of prostate cancer in men of Chinese ethnicity. This association was found by performing targeted genetic sequencing on the tumours of 1,016 Chinese patients before comparing the results with publicly available genomic data from The Cancer Genome Atlas, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Centre and Stand Up to Cancer cohorts’ representative of Caucasian men.

“The most important differences we observed were concentrated in castration-sensitive disease and included lower mutation rates in prostate cancer driver genes such as TP53 and PTEN among Chinese patients compared to the Western cohorts, which may partially account for the better prognosis observed in Asian men in this setting,” reported study author Dr Yu Wei, Fudan University Shanghai Cancer Centre, China.

This caused Wei to question whether the benefits demonstrated by current standard therapies in clinical trials with Western patients can be accurately translated to people of Asian heritage, due to varying treatment responses induced by different driver mutations. The results have highlighted issues surrounding ethnic diversity in clinical research.

In a castration-resistant setting, researchers carried out genetic testing on a group of 15 genes responsible for DNA damage and repair, including BRCA1 and BRCA2. This achieved a 30% reduction in the risk of death for patients with metastatic disease.

The researchers observed that mutation rates in genes predictive of response to these therapies were similar across races, regardless of the stage of the disease.

Changes in policy are needed

“This suggests that Chinese patients can equally benefit from PARP inhibitors provided they can obtain access to the treatment, which is why we propose that all Asian men with metastatic prostate cancer should receive genomic testing,” explained Wei.

“The genomic heterogeneity we see in metastatic, refractory prostate cancer can be understood as the result of tumour evolution under the pressure of therapy over several years, but it is noteworthy that variation between ethnicities was also observed in the primary tumour, confirming the existence of baseline differences in cancer development across races,” said Dienstmann.

The findings are consistent with other recent research on ethnic diversity in relation to prostate cancer. The results underline the importance of increasing the ethnic diversity in prostate cancer genomics databases to improve understanding of molecular epidemiology.

“These testing strategies need to be implemented in countries around the world,” concluded Dienstmann.