With her pioneering research in the field of oncology, Professor Tamara Lah Turnšek provides an insight into the Slovenian perspective on medical cannabis and cannabinoids in oncology.

Speaking at the Europe CBD Expo, Professor Tamara Lah Turnšek, previous Director of the National Institute of Biology in Ljubljana, Slovenia, elucidated our minds regarding the world of cancer and medical cannabis. Health Europa took the opportunity to interview Turnšek before the event, gaining a deeper understanding of the regulatory and research landscape regarding medical cannabis in Slovenia, along with the dynamically evolving role of cannabinoids in oncology.

Can you provide an overview of the current regulatory situation regarding the use of cannabis in Slovenia?

In Slovenia the regulatory situation is largely the same as other European countries. However, in 2014 the Slovenian government classified THC as a ubiquitous component of cannabis, present in varying degrees in all plant extracts. As a result, cannabis is classified as an illicit drug by Slovenia’s Ministry of Health and The Public Agency for Drugs and Medical Devices (abbreviated as JAZMP) in Slovenia. This has rescheduled cannabis from the Group I to the Group II category, which is considered less dangerous. Nevertheless, cannabis and the handling of cannabinoids along with research into its potential applications as a medicine is still strictly controlled as cannabis is still considered a dangerous drug.

Essentially there are two different aspects of cannabis use. One is the recreational aspect – which is not the topic that my research group is focusing on – but the second is the use of cannabis for medical purposes. In Slovenia all major and approved brands (such as Sativex) are available, but only via medical prescription from a medical specialist. This is an important development since the legislative change in 2014, so patients can now obtain permission to use these products for certain diseases and conditions.

Growth and production are very selectively permitted and approved only by adhering to very tedious procedures laid out by the Committee for Drugs at the Ministry of Health and JAZMP. Although medical cannabis is available with a prescription, I believe that the biggest problem is that medical doctors in Slovenia are still very reluctant to prescribe it for any kind of disease. Doctors are feeding back that there are no directives on how to use the drug and no clinical trials for disease states – unfortunately both are very true. Doctors understandably do not want to take a risk based on unknowns.

However, when the drug is being used it is done so with two types of diseases. Firstly, it is used in the palliative care of cancer patients, largely to combat pain and sickness due to chemotherapy. In this regard, medical cannabis is also considered because of its reportedly positive psychological effects, as well as its positive effects on appetite in cancer patients. Nevertheless, the usage of medical cannabis depends on the oncologist’s view, as it is still only being used to supplement standard treatment.

Most oncologists would never prescribe anything which is not approved by official medical agencies such as the FDA (Federal Drug Agency in the USA) or EMA (European Medical Agency in Europe) for specific clinical application. However, there are some oncologists who are more open to developing scientific reports and considering the accumulated evidence from the patients on claiming the ameliorating effects of cannabis on disease symptoms and progression.

Essentially, the view regarding the use of cannabinoids in oncology is not uniform and is subjective depending on the doctor; some will be willing to use it, but others say there are many more conventional drugs which can be used instead. For example, during palliative treatment for cancer opioids are frequently used which can cause toxic and even lethal side effects, whereas cannabinoids are not toxic at a similar dose. Nevertheless, it is important to differentiate that in the case of medical cannabis, patients who self-medicate are likely to be obtaining the plant extract from an unreliable source, with no guidance or instructions on how to use it correctly which is dangerous for their health.

The other disease where cannabis has proven its efficacy is epilepsy, particularly in children. At the Paediatric Clinic of the University Medical Centre in Slovenia, doctors are successfully treating certain types of epilepsy with medical cannabis. This is based on the positive effects they have witnessed first hand, such as fewer seizures which are less intense for example. These clinical studies are ongoing, and the results have already been published by Slovenian the medical team. Also, as is the case in every country there is the black market to consider. Nevertheless, here in Slovenia the patients are really pressing political parties to make medical cannabis regulation more liberal.

What can you tell us about the pre-clinical and/or clinical studies of cannabis and cannabinoids in Slovenia?

We are currently undertaking preclinical studies. The National Institute of Biology is the only public institution that I am aware of which has been granted authorisation to conduct medical cannabis research on human or animal derived materials, which we are doing in collaboration with MGC Pharmaceuticals. However, I understand that there are some institutions which have gained permission for cannabis extraction analysis.

The process of gaining research approval for medical cannabis involves applying to the National Committee of the Ministry of Health. Applicants are required to meet the special requirements of a committee regarding safety regulations and then (after a few months of paperwork) they receive official clearance. There are also some private companies that do have permission, especially foreign and multinational corporations who are sanctioned to produce various products containing cannabidiol (CBD) which is typically not a problem. However, when it comes to products containing THC the regulation is much stricter.

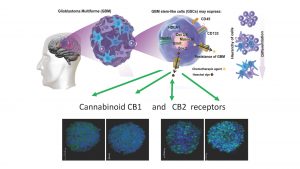

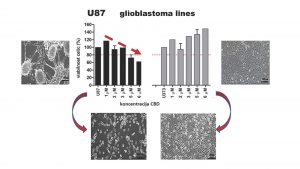

The current situation in our lab is that we have ongoing preclinical studies which are being supported by MGC Pharmaceuticals. The company is very keen on the studies we are conducting with a strong research emphasis of wanting to define cannabinoid applications in relation to tumours and organoids along with attempting to predict how these would act in vivo, when applied to patients. We particularly focus on how efficient cannabinoid applications are in eliminating tumour growth and how toxic or safe the drugs are in any particular patient. We are essentially testing cannabinoids in oncology with the hope that oncologists will use them in future, and that patients in need will receive a specified combination of cannabinoids that will be effective for them. That is the ultimate goal.

We began our research in 2018, and we are hoping that in a few years we will be able to create a protocol which will integrate preclinical studies into the lab (possibly with animals), to be ‘translated’ to clinics. We aim to set up a patient-adjusted platform for the clinical studies to show which patients respond well to treatment with cannabinoids with regards to lowering the growth or invasion of a tumour (to cause tumour regression).

There are many publications regarding in vitro results internationally and the number is growing very fast. Such research is describing the mechanisms of how cannabinoids work on the different types of malignant diseases, but there is very little outlining treatment which is personalised to the individual patients in clinics. This is the most important aspect: I strongly believe that not every patient can tolerate or benefit from safe doses of cannabinoids, just as they wouldn’t necessarily respond to any other pharmaceutical drug. Therefore, personalised treatment is very important if you want to see the effects.

From previous research, cannabinoids in oncology and medicine generally show therapeutic potential, but what is the evidence of the plant being an effective treatment for patients?

There are organic molecules in the plant, mostly cannabinoids, but also terpenoids and flavonoids in the cannabis plant that are biologically effective. Professor David Meiri at the Technicon institute in Haifa has identified the exact cannabinoid composition of different strains of cannabis with sophisticated chromatographic methodologies and is cultivating them in green houses (or so-called ‘cultivars’). Now we are now collaborating to investigate which combinations and compositions of the plant is most effective in a patient.

Extracts from the cannabis plant are of a complex composition comprising of natural organic compounds, therefore it is hard to standardise the plant as a classical pharmaceutical drug compared to aspirin for example. Therefore, researchers are working with either whole extracts, or with purely synthetic cannabinoids.

Synthetic cannabinoids have so far not shown the same level of efficacy as whole extracts which is what is known as the ‘entourage effect.’ There are now clinical studies starting with a relatively small number of patients examining cancers such as glioblastoma, but we do not yet have the results.

Animal studies on mice and rats have been demonstrated a 50-95% reduction and sometimes even a complete regression of tumour volume. There is hope that we will be able to translate these animal studies into human trials.

To conclude, there are three unknowns when it comes to the effectiveness of using medical cannabis to treat patients:

- Firstly, there is cannabinoid pharmacology which means how cannabis is metabolised, i.e. how the body processes the drug which may differ from patient to patient;

- Secondly, there is the unknown chemical transformation which could potentially damage normal tissues. For example, neurons being damaged by THC in developing brains; and

- Thirdly, how cannabinoid extracts (CBD or THC alone) would interact with other drugs used in conventional therapy; for example, using medical cannabis alongside chemotherapy. Such combined therapy could create synergistic activity and have the potential to stop tumour growth.

The third unknown relates to combining different treatments, for example, there is a drug called Temozolomide (TMZ) which is used to treat certain types of glioblastoma. TMZ in combination with CBD, or THC act synergistically on brain cancer cells which has been shown in several studies and we hope that such combination therapies will be explored in more depth in the future.

I personally do not believe that cannabinoids will ever be solely used to treat cancer, but instead will be used alongside a combination of drugs to complement existing treatment and therapies. What we really need is more funding for medical cannabis research to facilitate this.

What kind of framework would you like to see in place to help patients access medical cannabis more easily in Slovenia?

Firstly, we need to present the research to doctors but as previously mentioned they will require evidence from clinical trials and formal drug approval from medical agencies in order to use medical cannabinoids in oncology. I strongly believe that we will eventually gather enough scientific evidence that cannabinoids are useful not only for palliative application – but also for anti-tumour treatment. The most important thing is that doctors need exact and specific directives on how to treat certain types of cancer with medical cannabis.

Cannabinoid research in Slovenia is currently only supported by private funds. We appreciate the ongoing support of the multinational company MGC Pharmaceuticals Ltd. who in our case facilitate NIB investigations that will bridge the research, particularly in diseases where standard medicine progress is scarce such as glioblastoma. On the other hand, it would be necessary for the Slovenian government – specifically the ministries responsible for science and health – to collaborate and jointly increase available funds into cannabinoids, as there is increasing public demand for medical cannabis consumption.

Nevertheless, it is my strongly held opinion that patients should gain access to medical cannabis only via medical doctors, and to only consume well defined non-toxic products produced and tested under good laboratory standards. I believe self-growing and self-medication can potentially cause a lot of damage. At present, patients can purchase products and treatments which may not even contain the correct levels of cannabinoid or even any cannabinoid at all, which may endanger their health.

It is also important to understand that the older generation of doctors often do not have and do not want to gain knowledge regarding medical cannabis. Typically, they do not advise patients to use such a treatment except for in the case of palliative care. However, we are seeing more and more anecdotal cases in some patients where medical cannabis has been effective. I understand that doctors themselves are torn between the stigma and negative connotations on the one hand and their duty to help patients in need on the other.

I believe the negative attitudes regarding medical cannabis will change based on the emergence of scientific and clinical evidence, and we will slowly embrace cannabinoid research and treatment.

Professor Tamara Lah Turnšek,

Director of National Institute of Biology

http://www.nib.si/eng/