In this article, Marc Davis of Capital Markets Media discusses the efficacy of COVID-19 antigen tests.

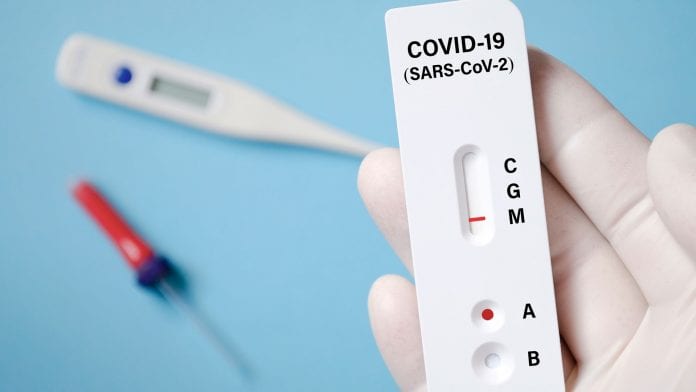

It was supposed to be a big breakthrough in the battle to contain the global COVID-19 pandemic. Admittedly, the use of inexpensive diagnostic screening devices has facilitated mass testing at point-of-care medical facilities, as well as airports, schools, offices, and other real-world settings. However, these so-called antigen ‘test kits’ are increasingly being criticised for their lack of accuracy.

Nonetheless, these newly-commercialised screening tools have been pressed into service on a widespread basis in recent months in both the UK and North America. But that is fast changing – at least in the US.

The greatest appeal of this far-from-perfect screening methodology is that it can be accurate in detecting COVID-19 in people with noticeable symptoms. However, this form of screening is not performing well in identifying people with a low viral load, including people who are pre-symptomatic or asymptomatic.

This is particularly problematic. At the very least, public health officials waste valuable resources by unnecessarily tracing person-to-person contacts in the instance of false positives. Worse still, false negatives may allow some people to unwittingly become so-called super-spreaders and to contaminate environments that have previously been kept virus-free.

Sounding the alarm

Health agencies across North America are now sounding the alarm about false positive readings generated by antigen tests, as well as a smaller percentage of false negatives.

In particular, a misdiagnosis can have especially dire consequences for the aged, they are warning. This demographic represents society’s most vulnerable citizens, involving two out of every five COVID-19 fatalities in North America.

Furthermore, in a recent independently conducted study, it was found that the average “sensitivity” (ability to detect the virus) of a handful of recently-commercialised antigen tests was only 56.2%. Another recent study found that the “true positive” rate of the evaluated rapid antigen test, in the case of asymptomatic patients, was less than 32%, versus a laboratory-based PCR test.

Among the most vocal critics of antigen tests are several high-profile trade organisations for laboratory technicians. They include the Berlin-based Accredited Laboratories in Medicine (ALM), which represents 25,000 German medical laboratory professionals.

Its CEO Michael Müller explained his organisation’s concerns in a recent media interview: “In the right situation, and when used critically, the antigen test is a good tool. But antigen tests can only be a supplement to the test strategy. Their informative value stands or falls with the question of what can be deduced from a result: if a person has a large amount of the virus, the test is relatively reliably positive. If it asymptomatic, the result could be false negative.”

Such concerns are also shared by the World Health Organization (WHO), which has yet to endorse any antigen-based rapid diagnostic tests for respiratory infections because of their tendency to be inaccurate.

These views are also being shared by leading North American health officials. For instance, Dr Supriya Sharma, a senior advisor at Health Canada, recently told the media: “A test that provides too many false negative results may lead to individuals not isolating as they should, and potentially more people being exposed to the virus. And a test that provides too many false positive results could lead to people needlessly self isolating.”

Even the manufacturers of these tests have cautioned that their products are not ideal for testing people with few or no symptoms.

For instance, Abbott Lab’s antigen test is only designed to detect people who are symptomatic, while the company warns the test alone does not confirm a diagnosis. The information sheet that accompanies the product says the following: “Negative results don’t preclude SARS-CoV-2 infection and they cannot be used as the sole basis for treatment or other management decisions.”

Nonetheless, Abbott’s product has been presaged into service for frontline detection after the pharma giant recently received emergency approval from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). That said, the FDA has also sounded off on the inherent drawbacks of such tests. A recent press release offered the following caution: “In general, antigen tests are very specific but are not as sensitive as molecular tests. Due to the potential for decreased sensitivity compared to molecular assays, negative results from an antigen test may need to be confirmed with a molecular test prior to making treatment decisions.”

Most recently, the FDA said it is alerting clinical laboratory staff and healthcare providers that false positive results can occur with COVID-19 antigen tests.

It is therefore now showing a reluctance to authorise emergency use for newcomers to the antigen screening market, after approving the first antigen test in May.

Ushering in Point-of-Care diagnostics

What exactly are the molecular tests that the FDA is referring to? Typically, they entail a laboratory-based procedure that magnifies the virus’ genetic material to detect and measure its viral load, no matter how small.

Currently, the gold standard of today’s COVID-19 testing is known as a polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Nasal swabs or saliva samples can be definitively tested this way, involving skilled laboratory technicians who are able to amplify any viral markers.

The key advantage of this extremely accurate testing is that it even allows for the detection of tiny quantities of viral particles and yields quantitative data, along with the qualitative results. However, PCR testing is relatively expensive (ranging between the US $50-$150 per test, or £35-£105) plus testing capacity throughout Europe and North America is also seriously limited and constrained by backlogs.

Despite these logistical challenges, PCR testing is well worth the cost because it is far more effective than antigen-based screening at early detection, which does not amplify the virus the way PCR tests do. This explains why people are willing to wait in line for testing for hours on end, even though it takes an average of 34 hours to generate a definitive result in the UK.

What is the solution to bringing PCR testing to the masses?

Hugh Rogers, the CEO of Canadian start-up biosciences company XPhyto Therapeutics, suggests the ubiquitous adoption of portable PCR devices at point-of-care facilities will prevent government testing procedures from continuing to produce so many false positives and false negatives from portable antigen tests.

His company is launching a single-cycle, saliva-based PCR kit that can be used to accelerate the processing times in laboratory-based PCR devices, as well as portable PCR testing equipment.

“Since the beginning of the pandemic, we have been operating on the presumption that molecular tests will be more sensitive and specific than comparable antigen-based systems across a range of patient populations. The emerging third-party clinical data supports our strategy,” he says.

“So, we are targeting commercial launch of our saliva-based molecular tests, both the rapid RT-PCR diagnostic test and the ultra-rapid disposable screening test in Europe in Q1 2021.”

Breaking the chains of transmission

As countries tentatively re-open their economies, there is growing consensus that on-the-spot testing on a population scale will be required to keep economies open while still protecting the world’s population of nearly eight billion.

The advent of portable or micronised PCR diagnostics – as well as cheap, but highly accurate molecular screening products for the consumer market – may yet prove to be the death-knell for less reliable antigen-based testing.

Indeed, the presumed ubiquitous adoption of PCR test kits that are considered extremely accurate, as well as fast, should ultimately prove critical fore monitoring, managing and mitigating new outbreak hotspots so that global health authorities can finally break the chains of transmission.

In turn, this should hopefully allow communities and economies to restore some semblance of normalcy to a world that has been traumatised by this latest coronavirus pandemic.

Marc Davies

Guest author

Capital Markets Media