The reality of healthcare in 2020 is that innovations that can have a positive impact on patient care aren’t always readily available to those who would benefit the most.

Take for example osteoporosis, where almost half of patients who suffer an osteoporotic hip fracture have experienced a previous osteoporotic fracture, but most of these patients did not receive treatment that would have reduced the risk of hip fracture after that initial fracture.1,2 The warning sign (the initial fracture) was there but not acted upon, and so they didn’t get access to the treatment or services that could have reduced their risk of a second fracture. Last year, a policy brief 3 written for the World Health Organisation (WHO) stressed this point, arguing that “there is need for responsible innovation to ensure that the benefits of innovation are widely distributed and shared, are sustainable and meet societies’ needs more broadly”.

The policy brief gives a stark warning: “health systems in Europe are facing the combined challenge of increasing demand due to a rising burden of chronic disease and limited resources”. This challenge is most notable in balancing the needs and services available to those in their later years.

With the number of people in the world aged 60 years or over projected to grow by 56 percent between 2015 and 2030,4 innovation must adapt to these broader demographic needs, including support for age-related conditions such as fragility fractures. As osteoporosis typically occurs in people over the age of 50 and the world’s population is living longer, the societal burden of the disease is expected to increase.5 Current statistics suggest that 1 in 3 women and 1 in 5 men aged over 50 will experience a fragility fracture because of osteoporosis.6 Innovation should focus on early diagnosis and prevention of future fractures; too many patients remain undiagnosed and untreated today, disconnected from the healthcare professionals who can help manage their disease, meaning they remain at risk of fractures that can lead to disability, loss of quality of life, and premature death.5

We must recognize the innovation from the last few years for the management of osteoporosis and prevention of fragility fractures and reflect on where these innovations have been applied and where more can be done.

In the 1950s, pioneers developed bone histomorphometry 7 as a way of exploring various metabolic bone diseases. Since then we’ve seen innovations in the field, including use of histomorphometry in diagnosis parameters, recommendations for the assessment of fragility fracture risk using clinical risk factors,8 considerable advances in imaging 9 and the introduction of fracture risk assessment tools, such as the FRAX® algorithm,10 to name a few.

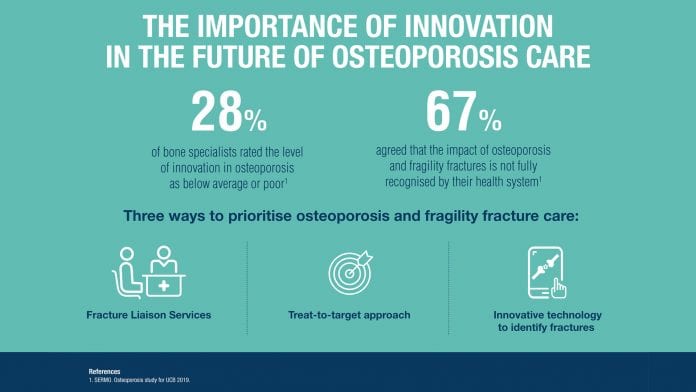

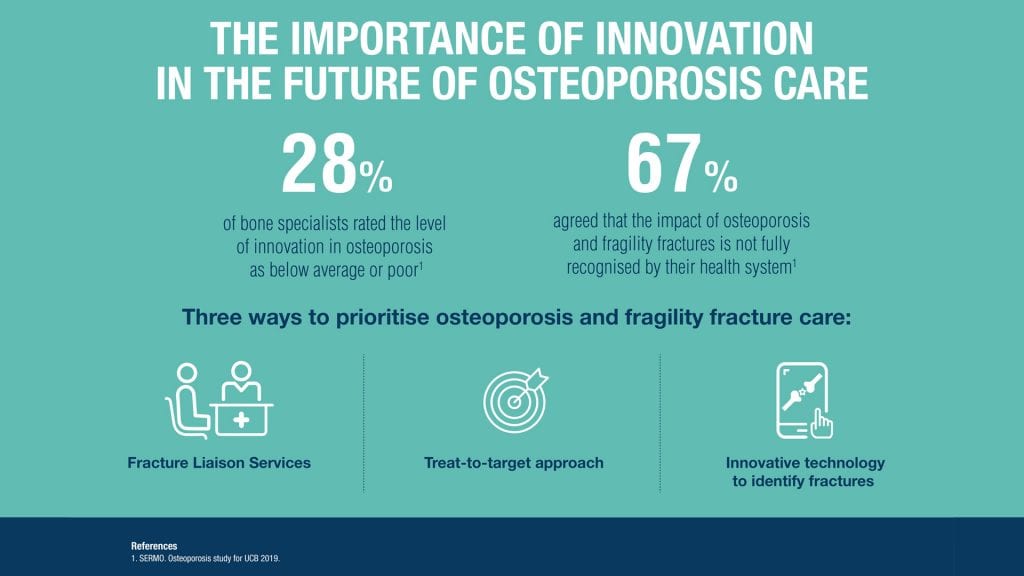

Ongoing research is essential to keep the field moving toward optimal osteoporosis management and fracture prevention, but how much progress has been made with recent innovation in osteoporosis? Research conducted by UCB, showed that over a quarter (28%) of bone specialists rated the level of innovation in osteoporosis as below average or poor and, they agreed that health systems are not doing enough to support.11 If we continue on this path, millions of people risk missing out on an acceptable quality of later life as they age. Ageing is inevitable, but how we age is not.

In order to meet the requirements of the WHO ‘responsible innovation to meet societies’ needs more broadly’,1 what more needs to happen to encourage innovation in osteoporosis?

A few years ago, we saw a welcome shift in the way osteoporosis is managed with the implementation of the Fracture Liaison Service (FLS). Best practices like the FLS have already undergone rigorous improvement over time, and their benefit is already widely acknowledged.12 More uptake of these services will provide solutions to the disconnect between patient and healthcare professional.

In addition to best practice processes like an FLS program, patients and physicians alike could benefit from a more individualized approach to treating and monitoring osteoporosis and fracture risk. In recent years, working groups13,14 and expert consensuses15,16 have expressed the potential benefit of a treat-to-target strategy to reduce the risk of fragility fractures. We can learn from other therapeutic areas which have benefited from a disease-specific treat-to-target approach to individualise the treatment of each patient based on their probability of reaching a treatment goal. These groups have commented that progress toward reaching the patient’s goal would include periodic and systematic assessment.13

For physicians and their patients with osteoporosis, this could open up a new and refined approach to use existing therapies. Ideally, using biomarkers that are reliable, easily measured and cost effective and setting targets that are realistic, adaptable and have evidence of the benefits, could result in a strategy to help reduce fragility fracture risk while providing important near-term feedback to patients that their treatment is making a difference.17

Technology innovation can also help identify patients at high risk of fracture before they even know they have an issue. Over 1.4 million patients each year suffer from vertebral fractures;18 tools utilizing artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms over existing patient images could help to identify patients susceptible to future fractures and lead to more effective clinical intervention, ultimately driving towards reducing the co-morbidities associated with osteoporosis.

To meet the WHO call for responsible innovation and ensure the benefits are widely shared, sustainable and meet societies’ needs, we need health systems and policy makers involved in bringing these innovations to life, ensuring osteoporosis is no longer overlooked and under prioritised. Tried and tested services such as the FLS should be implemented as widely as possible, new approaches should be considered and corporations and healthcare systems should invest in treatments, processes and devices, all with patients’ needs at the forefront to make innovation happen within osteoporosis.

Brandon Drew, Vice President & Global Head of Bone, Immunology Solutions at UCB Pharma SA

References

- Port, L., Center, J., Briffa, N.K. et al. 2003. Osteoporotic fracture: missed opportunity for intervention. Osteoporosis International 14: 780–784.

- Edwards BJ, Bunta AD and Simonelli C et al. 2007. Prior fractures are common in patients with subsequent hip fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 461: 226-230.

- Nolte E. How do we ensure that innovation in health service delivery and organization is implemented, sustained and spread? World Health Organisation [Online]. Available at: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/380731/pb-tallinn-03-eng.pdf?ua=1 (Last accessed February 2020)

- Global Ageing Times. Population ageing: main facts. [Online] Available at: http://www.globalagingtimes.com/aging/population-ageing-main-facts/18971 (Last accessed February 2020).

- IOF. Impact of Osteoporosis. [Online] Available at: https://www.iofbonehealth.org/impact-osteoporosis (Last accessed February 2020).

- Ström O, Borgström F, Kanis JA, et al. 2011 Osteoporosis: burden, health care provision and opportunities in the EU: a report prepared in collaboration with the International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF) and the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industry Associations (EFPIA). Arch Osteoporos. 6:59–155.

- Jee WS. 2005. The past, present, and future of bone morphometry: its contribution to an improved understanding of bone biology. J Bone Miner Metab. 23 Suppl:1–10.

- WHO Scientific Group on the Assessment of Osteoporosis at Primary Health Care Level. Technical Report. WHO Press; 2008.

- Genant HK, Jiang Y. 2006. Advanced imaging assessment of bone quality. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1068:410–428.

- The University of Sheffield. Fracture Risk Assessment Tool. [Online] Available at: https://www.sheffield.ac.uk/FRAX/ (Last accessed February 2020).

- SERMO. Osteoporosis study for UCB 2019.

- National Osteoporosis Society. Fracture Liaison Service Implementation Toolkit Service Improvement Guide. [Online] Available at: https://theros.org.uk/media/1831/flsit-service-improvement-guide-v2-11.docx (Last accessed February 2020).

- Kanis JA, McCloskey E, Branco J et al. 2014. Goal-directed treatment of osteoporosis in Europe. Osteoporos Int. 25:2533–43;

- Cummings SR, Cosman F, Lewiecki EM et al.2017. J Bone Miner Res Goal-Directed Treatment for Osteoporosis: A Progress Report From the ASBMR-NOF Working Group on Goal-Directed Treatment for Osteoporosis. 32:3–10

- Nogués X, Nolla JM, Casado E et al. 2018. Spanish consensus on treat to target for osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 2018;29:489–99;

- UCB data on file. European expert consensus survey

- Lewiecki E, Cummings S, Cosman F et al. 2013. Treat-to-target for Osteoporosis: Is Now the Time? The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 98: 946–953

- Johnell O, Kanis JA. 2006. An estimate of the worldwide prevalence and disability associated with osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int. 17:1726-33