Introducing DRUID (DRiving Under the Influence of Drugs) the public health app testing for cannabis – measuring your level of competency essential to skillful driving.

Consuming cannabis affects the body and mind in many different ways. Of particular concern is the functional impairment that can result, comprising slowed reaction time, reduced hand-eye coordination, poorer balance, and difficulty performing divided attention tasks. Some people use cannabis to experience a ‘high’ and become too impaired to drive safely, while others consume cannabis for medical reasons and may want to avoid its impairing effects. Being able to reliably measure testing for cannabis and one’s own level of impairment has been impossible – until now.

DRUIDapp, Inc. has developed a new public health app that provides an objective measure of impairment due to cannabis or any other source such as alcohol, prescription drugs, illicit (‘street’) drugs, polydrug use, sleep deprivation, fatigue, concussion, and cognitive or physical decline due to illness or aging.

The app is named DRUID® – an acronym for ‘DRiving Under the Influence of Drugs,’ though the app can be used for many purposes, not just to reduce drug-related traffic crashes. The current personal-use version of DRUID functions on both the iOS and Android platforms and is available now in both the App Store and Google Play.

How does DRUID work?

Taking only two minutes, DRUID calls on users to perform four tasks which test their reaction time, decision making ability, hand eye coordination, time estimation, and balance, all of which are basic competencies essential to skillful driving and that research studies have found to be impaired following alcohol, cannabis, or opioid use (Bondallaz et al., 2016; Downey et al., 2013; Jongen, Vuurman, Ramaekers, & Vermameeren, 2014; Sewell et al., 2013).

Three of the tasks are performed under conditions of divided attention. Hundreds of measurements are integrated statistically using a proprietary algorithm and then transformed to an overall impairment score that can range from 0 to 100. Most scores fall between 30 and 70. Absent any impairment, a typical baseline score for DRUID is generally in the range of 32 to 42.

The data collected to date indicates that DRUID is an excellent measure for tracking impairment after alcohol or cannabis consumption. For example, DRUID scores show the highest level of impairment within 30 to 45 minutes of beginning cannabis inhalation, and then decrease over a period of 2 to 3 hours, as would be expected as the body processes its psychoactive components.

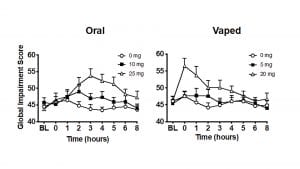

DRUID is being employed by cannabis investigators from several US universities. One of the top cannabis researchers, Dr. Ryan Vandrey of the Johns Hopkins University Medical Institute, and his colleagues examined the relationship between dosage-controlled cannabis administration and DRUID impairment scores.

Their data, displayed in Fig. 2, show that the app is able to discriminate impairment resulting from different levels of cannabis consumption, for both vapourised cannabis and edibles, specifically 0mg (placebo), 5 mg, and 20mg (vapourised) or 25 mg (edible). Additional research using DRUID is being conducted by investigators based at the University of Kentucky and Yale university.

DRUID – for personal safety

Knowing their impairment score, the app users can choose not to drive, perform safety-sensitive work, or engage in other potentially dangerous activities if they decide they are too impaired to do so. Before DRUID, there was not an accurate and reliable way for individuals to gauge their level of impairment, leading many people to overestimate their capacity to drive or work safely and thus putting themselves and others at risk of harm.

DRUID can also make a substantial contribution to medical cannabis practice. As is the case for many prescribed medications, using cannabis as prescribed may lead some patients to experience functional impairment. This possibility is often a source of considerable anxiety for patients inexperienced with cannabis who are rightfully worried about the impact of the drug’s physiological and psychological effects on their ability to drive, work, or perform other everyday tasks.

However, by using DRUID medical providers can work with their patients to identify the best dosage for treating their symptoms while also producing the least impairment possible. Of course, DRUID also provides a way for patients to assess the level of impairment they are experiencing after taking their medication, after which they can postpone driving or other potentially dangerous activities until it is safer.

DRUID – for worker safety

Worldwide, hundreds of millions of workers are in safety-sensitive jobs, including transportation, utilities, construction, manufacturing, warehousing, oil extraction and refining, mining, chemical production, public safety, private security, medicine, and many others. The impact of alcohol and other drug use on worker safety is a long-standing concern but has taken on even greater importance as the movement to legalise cannabis continues to gain momentum in the US and around the world.

Understandably, many employers have sought to protect their company or agency by requiring drug testing as a condition of employment or by conducting random drug tests. Both of these practices might be defensible when employees are in safety sensitive jobs or an employer is otherwise justified in asserting a zero tolerance policy for any illegal substance use. In addition, employers may require drug testing in response to accidents or other work performance issues.

It is important to note that, where cannabis use has been made legal, an employer’s legitimate concern – with some exceptions – is not the employees’ cannabis use per se, but the functional impairment that might result. Obviously, pre-employment testing no matter its accuracy, cannot guarantee that, on a particular day, an employee was not impaired and therefore fit for duty.

Urine drug tests conducted at random or after an incident can detect the presence of parent compounds or their metabolites, but as noted in a recent Cochrane Review article (Els, Jackson, Milen, Kunyk, & Straube, 2018), “this does not necessarily correlate to the level of impairment,” meaning that “the presence of a positive drug test does not necessarily confirm that the worker was impaired at the time of the work-related incident or accident.”

Thus, it is clear that as cannabis is legalised around the world for medical and recreational use, the mere presence of cannabis-related compounds becomes irrelevant, and this drug testing approach will no longer have any value.

Blood testing is also of little or no value. THC (tetrahydrocannabinol) is fat soluble, and the THC stored in body fat can reintroduced into the bloodstream as long as 30 days following cannabis use, whereas its psychoactive effects last only a few hours (Compton, 2017). It is not surprising then that studies consistently report that “the level of THC in the blood and the degree of impairment do not appear to be closely related” (Compton, 2017). In short, THC concentration in the blood is not a valid indicator of impairment. High impairment can be found with low THC levels, and low impairment can be found with high THC levels.

Dräger, Inc. has developed a machine to analyse oral fluids for drugs of abuse, including cannabinoids, amphetamines, designer amphetamines, opiates, cocaine and metabolites, benzodiazepines, and methadone (Grünberg, 2019). The Dräger DrugTest® 5000 can detect the presence of THC in a just few minutes, in contrast to blood drug tests, which need to be analysed off site at a special facility. Very small amounts of THC pass from the bloodstream into saliva, which means that this test suffers from the same limitation as blood tests; it can detect recent cannabis use but cannot assess impairment.

Hound Labs, Inc. in Oakland, California developed the Hound cannabis breathalyser, which can quantify the amount of THC in the breath from recent cannabis use, according to the company’s product information (Hound Labs, 2019). Cannabix Technologies, Inc., based in Canada, states that the breathalyser it is developing will be able to detect cannabis use that occurred up to two or three hours prior to testing (Cannabix Technologies, 2019).

Their device would not measure cannabis consumed in a capsule. While it may be useful to in certain contexts to have a quick, reliable test that can detect recent cannabis inhaled use, the fact remains that THC levels found in the body are not a valid measure of impairment (Downs, 2016).

Employers who are justified in asserting a zero-tolerance policy for any illegal substance use, including cannabis, can use urine, blood, saliva, or breath tests for pre-employment screening and random drug tests, since finding any detectable amount of a drug related compound would represent a violation of that policy. In the majority of cases however, to enhance worker safety, employers should instead use a valid and reliable measure of actual impairment that could result from any number of causes.

DRUID can meet that need. Ideally, employers with workers in safety-sensitive occupations would require their employees to use DRUID at the beginning of their work shift to demonstrate that there is no evidence of impairment. Later, the employees could be required to use the app again within 30 minutes of a randomly chosen time to ensure their continued fitness to work.

DRUID – for road safety

Driving is a complex skill. As noted previously, cannabis use can result in slowed reaction time, reduced hand-eye coordination, poorer balance, and difficulty performing divided-attention tasks, making it more dangerous to drive particularly within an hour or two of consuming the drug (Sewell, Poling, & Sofuoglu, 2009). Even so, cannabis users do not show a greater incidence of traffic crashes (Compton, 2017).

This may be because they compensate for their impairment by driving more cautiously (Sewell et al., 2009), although they still might respond too slowly to a sudden emergency. It should be noted, however, that research has found that the risk from driving under the influence of both alcohol and cannabis is greater than the risk of driving under the influence of either substance alone (Sewell et al., 2009).

Police use the ‘Standardised Field Sobriety Test’ (SFST) to determine if a driver is impaired. The SFST has three parts: the horizontal gaze nystagmus (HGN), walk and turn, and one leg stand tests. The latter is designed to test balance (NHTSA, 2018). About a third of the neurons in the brain are in the cerebellum which controls balance, so disrupted balance due to substance use can be an indication of systemic cognitive and physical impairment.

A study by Papafotiou and colleagues (2005) found that SFST result correctly identified their driving performance as either impaired or not impaired ranged between 65.8% and 76.3% across two THC conditions. Of course, SFSTs are not administered under laboratory conditions, but in the real world by police officers who may deviate from the protocol they were trained. This could happen in a number of ways, e.g., by giving unclear instructions, asking the driver to repeat the walk and turn or one leg stand tests, or requiring additional tasks (e.g., reciting the alphabet backwards, counting backwards from a random number).

For each test, officers are trained to look for specified signs of impairment, recording points for errors. Defence lawyers frequently challenge a SFST result, because poor performance might be due to the driver’s medical condition, a physical limitation that does not impact their driving ability, or their nervousness after being stopped by the police officer.

For these reasons, a recent report from the Center on Media, Crime, and Justice at John Jay College lists DRUID as the only objective measure for determining impairment during a roadside traffic stop (Bitsoli, 2018). Research now underway will compare DRUID impairment scores against driving simulator performance. With this data in hand, establishing the DRUID app as a standard testing protocol will be a possibility for law enforcement agencies and eventual judicial approval.

Summary

The DRUID app is an innovative approach for assessing impairment, with the potential for reducing the number of traffic crashes and worksite accidents due to alcohol, cannabis, or other drug use or to any other causes of impairment. At a time when medical and recreational cannabis use has become legal in many jurisdictions, the inherent shortcomings of urine, blood, saliva, and breathalyser tests and the SFST establish the basis for DRUID emerging as an accepted best practice for assessing impairment.

References

- Bitsoli, S. (2018). Do we need roadside marijuana tests? The Crime Report, November 21, 20018. Accessed on September 15, 2019 at https://thecrimereport.org/2018/11/21/do-we-need-roadside-marijuana-tests/.

- Bondallaz, P., Favrat, B., Chtioui, H., Fornari, E., Maeder, P., & Giroud, C. (2016). Cannabis and its effect on driving skills. Forensic Science International, 268: 92-102

- Cannabix Technologies (2019). The breathalyser. Accessed on September 15, 2019 at http://www.cannabixtechnologies.com/thc-breathalyzer.html.

- Compton, R. (2017). Marijuana-impaired driving: A report to Congress. (DOT HS 812 440). Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Accessed on September 15, 2019 at https://www.nhtsa.gov/sites/nhtsa.dot.gov/files/documents/812440-marijuana-impaired-driving-report-to-congress.pdf.

- Downey, L.A., King, R., Papafotiou, K., Swann, P., Ogden, E., Boorman, M., & Stough, C. (2013). The effects of cannabis and alcohol on simulated driving: Influences of dose and experience. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 50: 879-886. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2012.07.016

- Downs, D. (2016). Don’t hold your breath for a marijuana “breathalyzer” test. Scientific American, November 7, 2016. Accessed on September 15, 2019 at https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/don-t-hold-your-breath-for-a-marijuana-breathalyzer-test/.

- Els, C., Jackson, T. D., Milen, M. T., Kunyk, D., & Straube, S. (2018). Random drug and alcohol testing for preventing injury in workers. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2018(1). Accessed on September 15, 2019 at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6491335/.

- Grünberg, F. The trail of saliva. Dräger Review, 107, 24-27. Accessed September 15, 2019 at https://www.draeger.com/Corporate/Content/draeger_review_107_special_2_drug_testing_the_trail_of_saliva.pdf

- Hound Labs (2019). Hound Labs partnered with Triple Ring Technologies to create the Hound® marijuana breathalyser. Accessed on September 15, 2019 at https://houndlabs.com/engineering/.

- Jongen, S., Vuurman, E., Ramaekers, J., & Vermameeren A. (2014). Alcohol calibration of tests measuring skills related to car driving. Psychopharmacology, 231(12):2435-47. doi: 10.1007/s00213-013-3408-y.

- National Highway Transportation Safety Administration (2018). DWI detection and standardised field sobriety test (SFST) instructor guide. Washington, DC: NHTSA. Accessed on September 15, 2019 at https://www.nhtsa.gov/sites/nhtsa.dot.gov/files/documents/sfst_full_instructor_manual_2018.pdf.

- Papafotiou, K., Carter, J. D., & Stough, C. (2005). The relationship between performance on the standardised field sobriety tests, driving performance and the level of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) in blood. Forensic Science International, 155(2-3), 172-178.

- Sewell, R. A., Poling, J., & Sofuoglu, M. (2009). The effect of cannabis compared with alcohol on driving. American Journal on Addictions, 18(3), 185-193.

- Sewell, R.A., Schnakenberg, A., Elander, J., Radhakrishnan, R., Williams, A., Skosnik, P.D., Pittman, B., Ranganathan, M. & D’Souza, D.C. (2013). Acute effects of THC on time perception in frequent and infrequent cannabis users. Psychopharmacology, 226(2):401-13. doi: 10.1007/s00213-012-2915-6.

Co-Authors

Michael Milburn PhD and William DeJong PhD

If you wish to reference this article, please use the following format:

Milburn, M. A., & DeJong, W. (2019). A Paradigm Shift in Impairment Testing for Cannabis: The DRUID® App.

Michael Milburn PhD

CSO & Founder

DRUIDapp Inc

+1 617 785 0353

mike@druidapp.com

https://druidapp.com

This article will appear in Health Europa Quarterly Issue 11, which is available to read now.