Health Europa Quarterly spoke to Dr Joanne Hackett, Former Chief Commercial Officer of Genomics England and Regional Board Member of Movement Health 2030, about how genomic sequencing is aiding preparedness and response to public health threats.

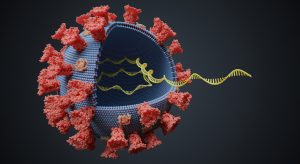

Genomic sequencing is a method scientists use to decipher the genetic material found in organisms or viruses. The significance of genomic sequencing tools was truly brought to the fore during the COVID-19 pandemic as researchers were able to observe any sudden changes (or mutations) in a virus’s genetic code which may give it an advantage over other variants of itself, for example, spreading faster or causing more harm to those it infects.

Mutations do not always result in a major change in a virus’s ability to spread or cause disease but if variants are left unchecked, they can become more prevalent in a population over a shorter period. Similarly, if a specific variant starts to have a widespread impact on a population, it may be classified as a variant of concern.

We spoke to Dr Joanne Hackett, Head of Genomic and Precision Medicine at IQVIA and Former Chief Commercial Officer of Genomics England, about how genomic sequencing and surveillance can support efforts to mitigate public health threats.

Can you describe the virus genome sequencing process and how it supports the detection and control of infectious diseases?

Virus genome sequencing has proved to be a key tool in the detection of SARS-CoV-2 variants in the current pandemic. Technically speaking, a virus is easy to sequence as it is so small compared to a human genome. The bigger challenges are the speed of sequencing and the importance of timely sharing.

The early sharing of genomic sequencing data from the novel pneumonia in China in early 2020 allowed the rapid development of diagnostic tests and, most crucially, the record-breaking development of vaccines.

The big global achievement was to scale up genomic sequencing to be able to deal with massive numbers of positive specimens and report them in national and global databases. There are currently over nine million SARS-CoV-2 genomes on the global GISAID database. The rapid uploading of sequences led to the identification of the major variants of concern – often initially given the names of the countries that first identified them due to effective surveillance. These are now more sensibly referred to via Greek letters, currently, Omicron is the most common.

What was the significance of ongoing viral monitoring during the COVID-19 pandemic? How have genomic sequencing surveillance strategies and sequencing technologies changed since the pandemic began?

The initial population scale viral genomic sequencing of genomes relied on academic consortia working with hospitals and public health agencies. In time, once the value of viral genomes was established, these academic efforts have been aligned with national testing strategies. The other major challenge has been robust sampling strategies and the ability to link viral genomes to patient data – including the date of infection and severity of the illness. Some countries have struggled to achieve this due to the separation of testing and sequencing facilities and concerns about data governance.

How did the UK’s surveillance system for new variants compare to other countries?

The UK was able to establish a very rapid viral sequencing capability through the work of the COG-UK Consortium led by Sharon Peacock and colleagues and relying on existing research capacity at the Sanger Centre, the Quadram Institute, and many others. This was funded by research agencies but was quickly connected to the main PCR testing laboratory network, the Lighthouse Laboratories. The data then flowed via existing academic databases into the four main public health agencies in the UK. At one time the UK had deposited over 50% of the sequences in the global databases and remains second only to the USA for total SARS-CoV-2 sequences.

The UK has also funded an initiative called the New Variant Assessment Platform that supports low- and middle-income countries to develop their own genomic sequencing and analysis capabilities and to support the biological characterisation of new variants using facilities in the UK.

Many of the capabilities used in the COVID pandemic are capable of being applied in AMR surveillance and response

How important is an international collaboration to the work of genomic pathogen surveillance and can you outline any challenges associated with this?

The pandemic has highlighted the importance of international cooperation and the sharing of data. COVID-19 relied on infrastructure developed to respond to pandemic influenza, including the GISAID database.

The importance of pathogen genomics was highlighted in several global initiatives during the pandemic that shaped the response to that and potentially any future pandemic threats. The WHO and G7 have recommended that all countries aimed to sequence 5-10% of COVID-19 cases, and that data be shared widely to track new variants of concern, drive enhanced responses, and inform plans for vaccination or modified vaccine composition.

Several countries have taken specific action to improve global cooperation. Under the UK’s G7 presidency, Sir Jeremy Farrar recommended a global network of expertise to provide a new ‘global pandemic radar’. This is being developed at the International Pathogen Surveillance Network led by the WHO. Germany has committed funding to a WHO Hub for Pandemic and Epidemic Intelligence in Berlin that will develop tools to detect and tackle new pandemic threats. Many countries are funding enhanced surveillance facilities as well as support from global initiatives like the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovation (CEPI) and the One Health initiatives on animal and agricultural threats.

How do you see the UK and Europe’s genomic industries developing in the future to support response efforts to public health threats such as antimicrobial resistance?

The industry has played a key role in the development of diagnostics, vaccines, and countermeasures and this has relied on genomics and advanced data analytics. Genomics and other industries are key partners in initiatives like the 100 Days Mission to accelerate the response to a new pandemic threat. Antimicrobial resistance is also a key public health priority requiring global action. Many of the capabilities used in the COVID pandemic are capable of being applied in AMR surveillance and response.

Dr Joanne Hackett

Head of Genomic and Precision Medicine

IQVIA

Former Chief Commercial Officer

Genomics England

https://www.linkedin.com/in/joannemhackett/?originalSubdomain=uk

https://twitter.com/joannehackett00?lang=en

This article is from issue 23 of Health Europa Quarterly. Click here to get your free subscription today.